COLOSSI OF MEMNON

Several of the inscriptions record the visits of family parties: the usual mention is of wife and children [...] and sometimes the voice of Memnon awakened in the thoughts of hearers a wish that a relative or friend might hear him, and the wish was duly written on Memnon's legs. With one of them hearing Memnon was Julia Balbilla (72 – 130), a Roman noble woman and poet. Leaving three graffitis in 130 AD while accompanying Roman emperor Hadrian and his wife Vibia Sabina. On the bottom left foot Balbilla inscribed to honour Amenhotep III.

Richard Pococke among the first to copy and translate the inscriptions.

"I, Balbilla, heard, from the speaking stone,

the divine voice of Memnon or Phamenoth.

I came here with our lovely queen Sabina,

when the sun held its course during the final hour,

in the fifteenth year of the emperor Hadrians’s rule, Hathyr was on its twenty-fourth day.

On the twenty-fifth day of the month of Hathyr."

In 27 BCE, a large earthquake reportedly shattered the northern colossus, collapsing it from the waist up and cracking the lower half. Following its rupture, the remaining lower half of this statue was then reputed to "sing" on various occasions – always within an hour or two of sunrise, usually right at dawn. The sound was most often reported in February or March, but this is probably more a reflection of the tourist season rather than any actual pattern.

The earliest report in literature is that of the Greek historian and geographer Strabo, who said that he heard the sound during a visit in 20 BCE, by which time it apparently was already well-known. The description varied; Strabo said it sounded "like a blow", Pausanias compared it to "the string of a lyre" breaking, but it also was described as the striking of brass or whistling. Other ancient sources include Pliny (not from personal experience, but he collected other reports), Pausanias, Tacitus, Philostratus and Juvenal. In addition, the base of the statue is inscribed with about 90 surviving inscriptions of contemporary tourists reporting whether they had heard the sound or not.

The legend of the "Vocal Memnon", the luck that hearing it was reputed to bring, and the reputation of the statue's oracular powers became known outside of Egypt, and a constant stream of visitors, including several Roman emperors, came to marvel at the statues. The last recorded reliable mention of the sound dates from 196. Sometime later in the Roman era, the upper tiers of sandstone were added (the original remains of the top half have never been found); the date of this reconstruction is unknown, but local tradition places it circa 199 and attributes it to the Roman Emperor Septimius Severus in an attempt to curry favour with the oracle (it is known that he visited the statue, but did not hear the sound).

Various explanations have been offered for the phenomenon; these are of two types: natural or man-made. Strabo himself apparently was too far away to be able to determine its nature: he reported that he could not determine if it came from the pedestal, the shattered upper area, or "the people standing around at the base". If natural, the sound was probably caused by rising temperatures and the evaporation of dew inside the porous rock.

Similar sounds, although much rarer, have been heard from some of the other Egyptian monuments (Karnak is the usual location for more modern reports). Perhaps the most convincing argument against it being the result of human agents is that it did cease, probably due to the added weight of the reconstructed upper tiers.

A few mentions of the sound in the early modern era (late 18th and early 19th centuries) seem to be hoaxes, either by the writers or perhaps by locals perpetuating the phenomenon.[citation needed]

The "Vocal Memnon" features prominently in one scene of Henrik Ibsen's Peer Gynt.

They also show up in Oscar Wilde's fairy tale "The Happy Prince."

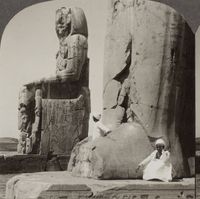

The Colossi of Memnon (Arabic: el-Colossat or es-Salamat) are two massive stone statues of the Pharaoh Amenhotep III, which stand at the front of the ruined Mortuary Temple of Amenhotep III, the largest temple in the Theban Necropolis. They have stood since 1350 BC, and were well known to ancient Greeks and Romans, as well as early modern travelers and Egyptologists. The statues contain 107 Roman-era inscriptions in Greek and Latin, dated to between AD 20 and 250; many of these inscriptions on the northernmost statue make reference to the Greek mythological king Memnon, whom the statue was then – erroneously – thought to represent.

The twin statues depict Amenhotep III (fl. 14th century BC) in a seated position, his hands resting on his knees and his gaze facing eastwards (actually ESE in modern bearings) towards the river. Two shorter figures are carved into the front throne alongside his legs: these are his wife Tiye and mother Mutemwiya. The side panels depict the Nile god Hapi.

The statues are made from blocks of quartzite sandstone which was quarried at el-Gabal el-Ahmar (near modern-day Cairo) and transported 675 km (420 mi) overland to Thebes (Luxor). The stones are believed to be too heavy to have been transported upstream on the Nile. The blocks used by later Roman engineers to reconstruct the northern colossus may have come from Edfu (north of Aswan). Including the stone platforms on which they stand – themselves about 4 m (13 ft) – the colossi reach 18 m (60 ft) in height and weigh an estimated 720 tons each. The two figures are about 15 m (50 ft) apart.

Both statues are quite damaged, with the features above the waist virtually unrecognizable. The southern statue comprises a single piece of stone, but the northern figure has a large extensive crack in the lower half and above the waist consists of 5 tiers of stone. These upper levels consist of a different type of sandstone, and are the result of a later reconstruction attempt, which William de Wiveleslie Abney attributed to Septimius Severus. It is believed that originally the two statues were identical to each other, although inscriptions and minor art may have varied.

The original function of the Colossi was to stand guard at the entrance to Amenhotep's memorial temple (or mortuary temple): a massive construct built during the pharaoh's lifetime, where he was worshipped as a god-on-earth both before and after his departure from this world. In its day, this temple complex was the largest and most opulent in Ancient Egypt. Covering a total of 35 hectares (86 acres), even later rivals such as Ramesses II's Ramesseum or Ramesses III's Medinet Habu were unable to match it in area; even the Temple of Karnak, as it stood in Amenhotep's time, was smaller.

With the exception of the Colossi, however, very little remains today of Amenhotep's temple. It stood on the edge of the Nile floodplain, and successive annual inundations gnawed away at its foundations – a 1840s lithograph by David Roberts shows the Colossi surrounded by water – and it was not unknown for later rulers to dismantle, purloin, and reuse portions of their predecessors' monuments.

The statues contain 107 Roman-era inscriptions in Greek and Latin, dated between 20-250CE; these inscriptions allowed modern travellers to connect the statues to the classical Greek and Latin literature. Many of the inscriptions include the name "Memnon".

They were first studied in detail by Jean-Antoine Letronne in his 1831 La statue vocale de Memnon considérée dans ses rapports avec l'Égypte et la Grèce and then catalogued in the second volume (1848) of his Recueil des inscriptions grecques et latines de l'Égypte. (Source: Wikipedia)